RESEARCH

From Women's

Empowerment

to Gender Equality (Part 1)

– Eliminating Gender

Inequality –

April 2025 (Japan)

From Women's Empowerment to

Gender Equality (Part 1)

– Eliminating Gender Inequality –

Focusing on "how to encourage women to demonstrate their abilities to the fullest,"

Shiseido has been promoting various measures to enhance women's empowerment,

such as changing awareness among superiors and women themselves,

as well as reforming work styles and employment practices.

As a result,there are many female leaders at Shiseido,

with the percentage of women in leadership positions in Japan exceeding 40% in January 2024.

We aim to increase this to 50% to fairly represent gender equality by promoting initiatives for women.

However, even among its various divisions and organizations, Shiseido still includes some highly homogenous organizations that lag behind in empowering women.

Therefore, we have investigated such organizations and utilized causal inference in statistics to examine the factors that contribute to gender inequality.

INDEX

01

What are some examples

of gender inequality?

Title 1:

There are no gender differences in terms of one’s ability to deliver results.

Analytical methods:

The analysis was conducted on X and Y organizations, which tend to be highly homogeneous. Individual performance over the past five years, 2018-2022, was identified to ensure a statistically valid sample size and establish a gender comparison on the ability to deliver results. We approached statistical causality through an "event study analysis" rather than concluding differences in male and female performance based solely on differences in performance, as one gender may be in a more performance-driven role than the other. Variations in outcomes were analyzed for all patterns when a role changed from male to female, from female to male, from male to male, and from female to female. We also examined "whether there is a difference in average performance by gender when given roles under the same conditions" by taking into account age, length of service, grade, and labor contract conditions and utilizing averages that mitigated individual differences in ability so that the analysis results would show differences by gender.

Analysis results:

For both X and Y organizations, the outcome values did not change at a statistically significant level before and after the change in gender of the person in the role “from male to female, female to male, female to female, male to male” (Figure 1). In other words, the results show that both men and women can achieve the same level of results if given roles under the same conditions, and that there are no gender differences in their ability to produce results.

Title 2:

There are gender differences in how "roles" are assigned.

Analytical methods:

Next, we examined whether there were gender differences in the way roles were assigned. The verification targeted roles that are challenging in terms of both quantity and quality. We extracted highly challenging tasks from the organizations' job descriptions and analyzed whether or not the subject held at least one highly challenging role at some point in the past five years from 2018 to 2022 for X and Y organizations, aligned by age, length of service, grade, and labor contract.

Analysis results:

In Organization X, there were no gender differences in how roles were assigned. On the other hand, in Organization Y, men were 13% more likely to be given more difficult roles (Figure 2). In other words, it was found that there were gender differences in terms of fairness in the way roles were assigned in some organizations.

Title 3:

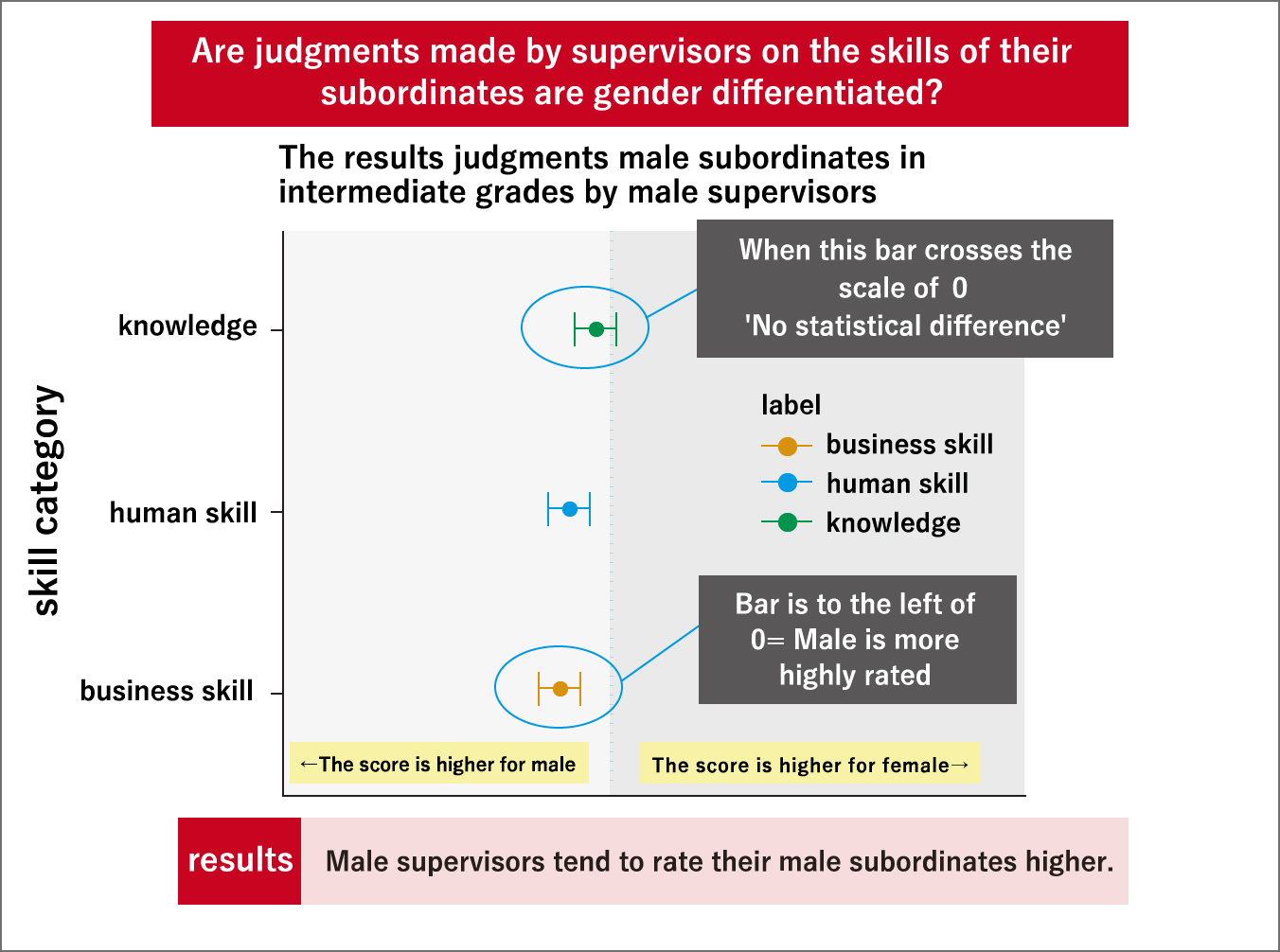

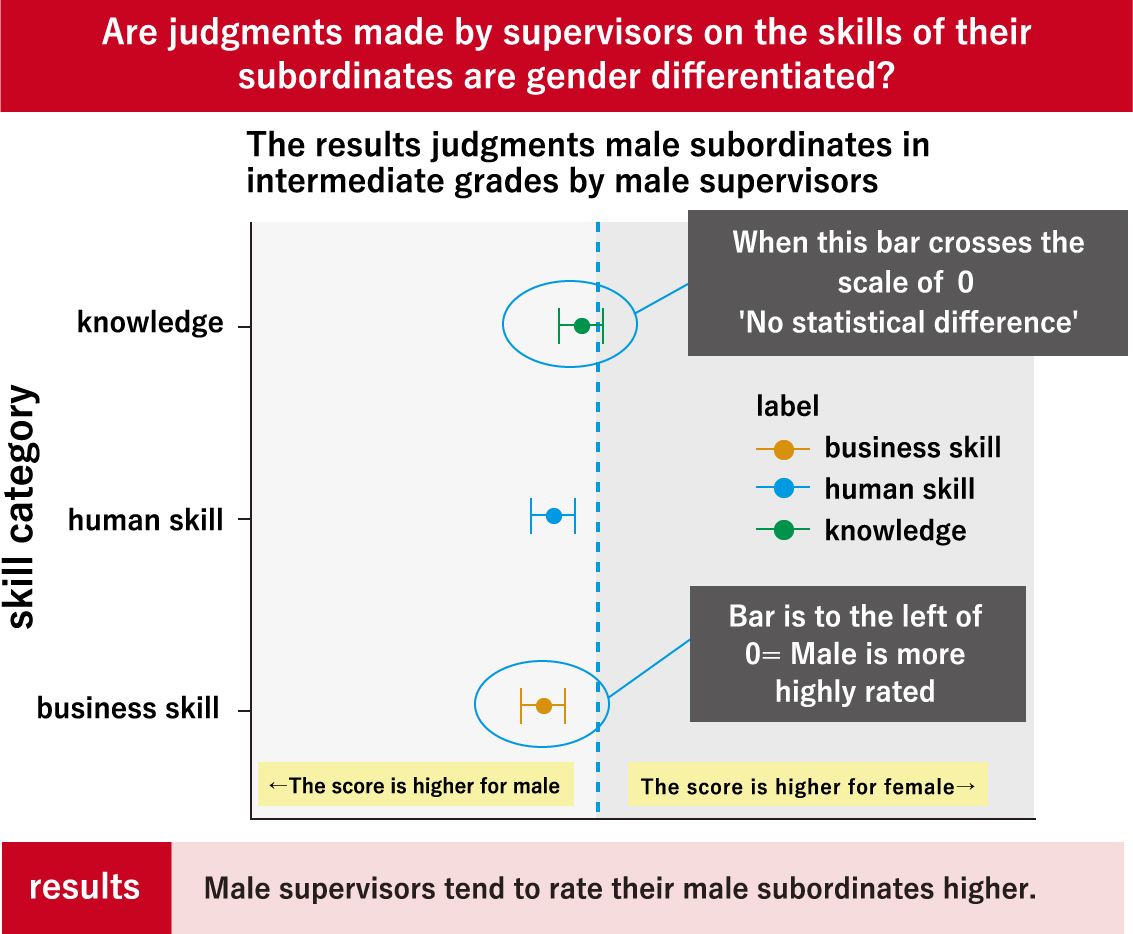

Judgments made by supervisors on the skills of their subordinates are gender differentiated.

Analytical methods:

Supervisors judge the competency of the skills of their subordinates on a 5-point scale for the purpose of advancing their development. We conducted a correlation analysis looking at the genders of the supervisor and subordinate for each grade based on the 2021-2022 skill judgment data for X and Y organizations.

Analysis results:

The grades analyzed included beginner, intermediate, and advanced. No statistical gender differences were observed in the beginner grade. For men in the intermediate grades, the ratings tended to be higher for all skills, while women in advanced grades tended to be rated higher in some skills. Overall, there were no gender differences in skill ratings. On the other hand, the results of the correlation analysis between the gender of the supervisor and that of the subordinate showed a statistically clear difference, with male subordinates in intermediate grades being rated higher by male supervisors compared to female subordinates (Figure 3). In other words, the results suggest that there is a gender difference in regards to giving higher ratings to same-sex subordinates in some grades.

by male supervisors

02

Identifying organizational biases

The results of validation 1-2 show that there were no gender differences in ability, but the probability of taking on more difficult roles was higher for men in some organizations. If taking on more challenging roles provides more growth opportunities, then "women may have fewer opportunities for growth." In addition, Title 3 found that for some grades supervisors tended to assign higher ratings to same-sex subordinates. So, why is there a difference in the way roles are assigned? And why do supervisors tend to give higher ratings to same-sex subordinates for some grades?

To answer these questions, we proposed two hypotheses, based on our belief that bias, a phenomenon in which judgments and decisions are biased due to "preconceptions" and "assumptions," may be the cause.

Hypothesis 1.

Communication Hypothesis

It is easier to communicate more closely with same-sex subordinates and to observe their behavior. In this environment, subordinates may also be more likely to seek advice from their supervisors and be offered better career opportunities.

Hypothesis 2.

Unconscious Bias Hypothesis

Stereotypes related to the gendered division of labor due to fixed assumptions and images held about the genders may affect the way they think about gender roles. They may also unconsciously judge subordinates of the same gender highly and those of the opposite gender more harshly.

Hypothesis 1.

Communication hypothesis verification

Analytical methods:

One of the reasons for the tendency to assign higher scores to same-sex subordinates may be "gender homophily." It is possible that male supervisors communicate more with male subordinates and female supervisors communicate more with female subordinates, and as a result, subordinates of the same gender have more opportunities to showcase their achievements and receive mentoring.

We tested whether "gender homophily" was occurring in X and Y organizations by using data on the average formal 1-on-1 time between supervisors and subordinates from January to November 2023. If the 1-on-1 time between male supervisors and subordinates was longer than for female subordinates, and if the 1-on-1 time between female supervisors and subordinates was longer than for male subordinates, the hypothesis would be considered to be valid.

*Homophily: A phenomenon in which "people tend to connect better with those with similar attributes.” This is a main focus in social network research. In particular, the phenomenon in which men tend to connect better with men and women tend to connect better with women is called gender homophily.

Analysis results:

For both male and female supervisors, it was found that more 1-on-1 time was spent with male subordinates than female subordinates. There was a slight advantage of having a female supervisor for female subordinates, but there was no statistical difference (Figure 4). In other words, the communication hypothesis was not substantiated in X and Y organizations.

Next, we will test Hypothesis 2, the Unconscious Bias Hypothesis. The results of the verification will be published in the next report.

03

Eliminating gender inequality

Dispelling unconscious bias in an organization can be difficult. It is also true that bias can create gender differences in the thinking of supervisors and lead to gender inequality in key personnel decisions. In addition, disadvantaged employees may experience lost growth opportunities and delays in their career development, putting a "halt" to their career advancement.

This is why it’s essential to be aware of biases. It is important to understand the positions and perspectives of people from diverse backgrounds. This will ensure that diverse human resources (diversity) have fair opportunities (equity) regardless of gender and lead to a state where all employees in the organization are respected and can demonstrate their abilities and play an active role (inclusion). Thus, the key to promoting woman's empowerment lies in gender equality. We need to move beyond the era of focusing on one gender and implementing support measures and face the challenge of eliminating gender inequality.

In future research, we will compare the biases of diverse organizations with those of homogeneous ones. Does increasing organizational diversity contribute to dispelling bias? Are there ways to mitigate bias in homogeneous organizations? We will examine these themes in the next issue.

Statistical Analysis: Shintaro Yamaguchi (University of Tokyo), Yoko Okuyama (Uppsala University), Chihiro Inoue (University of Tokyo), Chiho Taniguchi (University of Tokyo).

Comment from Shintaro YAMAGUCHI

Professor in the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo

Our collaboration with DE&I Lab has already produced some interesting discoveries, and the first year of the project has been completed smoothly. As a starting point for our research, we began by finding gender gaps within the company. Shiseido is known as a "company where women are active," so there were not as many obvious gender gaps as seen in other Japanese companies. For example, as the verification of the "Communication Hypothesis" revealed, most of Shiseido's supervisors seem to treat their subordinates equally regardless of their gender.

However, as the analysis proceeded, it gradually became clear that even Shiseido is not immune to gender gaps. For example, in Title 2, it was found that some organizations had gender gaps with regard to the division of work roles. It was also suggested in Title 3 that there was gender bias in the evaluation of subordinates' skills in some organizations. These results indicate that human capital may not be properly valued and appropriately assigned.

In the future, we will be looking at where gender gaps remain in the company, what causes it, and how it affects the company's performance. We will also continue our research on identifying how to eliminate bias. The goal of the DE&I Lab and our research team is to gain the knowledge necessary to help create a diverse, high-performing organization. We will seek to ensure that all people can fully demonstrate their abilities, feel a sense of fulfillment in their work, and achieve excellent results.

Shintaro YAMAGUCHI

Professor in the Faculty of Economics at the University of Tokyo

Research Field: Labor Economics, Economics of the Family

Research Theme: Professor Yamaguchi has expertise in empirical research on labor economics and economics of the family. He has attracted attention not only from academia but also from the media, including for his column in the Nikkei newspaper.